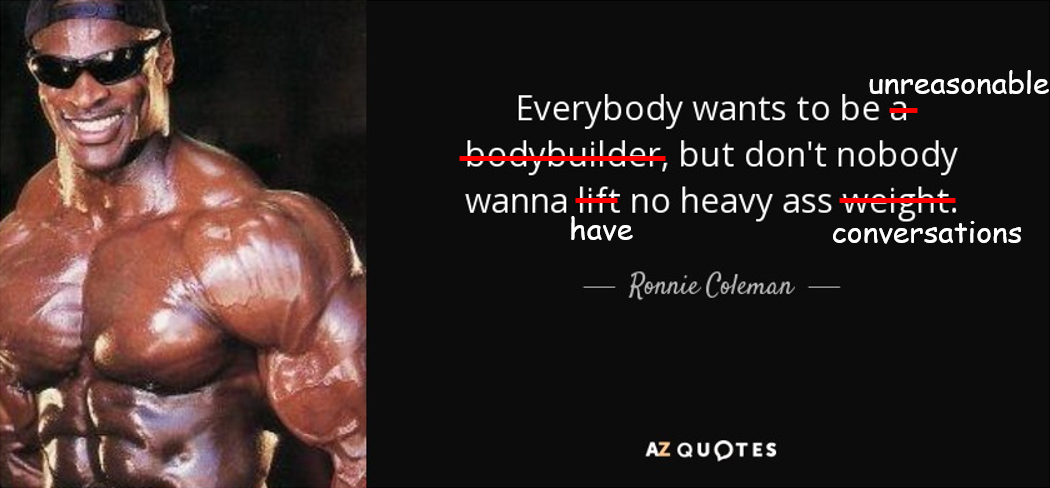

A couple months ago, I read this post by Spotify’s CEO, Daniel Ek, where he shared a quote by George Bernard Shaw:

“The reasonable man adapts himself to the world; the unreasonable man persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.”

It aligned with everything I’ve learned about scientific and cultural progress, and how new ideas typically come from people at the fringes of the current zeitgeist. So, like Ek, I adopted this as a guiding motto. I began to speak and act without fear of judgment, and was pleasantly surprised to find this opened many new doors. However, it also led to some unexpected experiences that I’d like to share.

Resistance to new ideas is typically expected from older generations or strangers, but it can be extremely disorienting when it comes from a friend or significant other. Teenage years give one plenty of practice debating with parents, teachers, or mentors. Unfortunately, it can be much harder to deal with negative reactions to a new idea when they come from someone with whom you were presumably intellectually well-aligned. And, if the idea digs deep enough, it can, with immediate effect, create a painful emotional rift with someone you hold dear.

Being unreasonable is hard. Most people, especially young people, like an element of adventure or weirdness in their lives. But get too weird, make people question some of their fundamental beliefs, and you risk alienation. The ensuing feelings of loneliness or isolation will not be easy. Believing and acting on a new and truly important idea will likely require immense courage and strength to hold steady amid the stormy seas of social and emotional pressure. You will be alone and scared. Fortunately, if you have a good reason to believe in your idea, and follow through with it, the storm will clear out.

Progress requires a delicate balance between unreasonable ideas and reasonable discussions. Pick a problem, dig to its core in search of truth, no matter how different, wrong, or scary the idea might seem. Be truly unreasonable in this search for truth but never forget that discussion and criticism is where great ideas are formed. And engaging in productive discussions will require a degree of agreeableness so that you can properly understand other perspectives. Discussions of this kind will most likely result in an improved version of your original idea.1

Finally, one can and should choose where to be unreasonable. Pick a couple things you truly care about and go all-in on them. For everything else, simply let things be. Being unreasonable and disagreeable about everything is only a recipe for becoming a bitter, resentful, and very unhappy person.

Personally, I would describe the effect of George Bernard Shaw’s idea on me as intense yet extremely formative. In my “unreasonable” search for truth about the things I care and I find meaning in, some relationships I cared deeply about have unravelled. I am reminded of Drake’s line in “Fair Trade”:

“I been losing friends and finding peace

But honestly that sounds like a fair trade to me.”

This process has been painful, but there is no other way. And now, as calmer seas prevail, I find myself with a sense of meaning and purpose that’s stronger than ever before.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to all my friends, family, and mentors who have encouraged me to keep pushing for what I believe in, even when I’m unreasonable about it :)

Related

- The Structure of Scientific Revolutions by Thomas Kuhn.

- The Beginning of Infinity by David Deutsch. Read my notes on the book here.

- The Deutsch Files, where Naval Ravikant and Brett Hall interview David Deutsch about his views on knowledge creation, scientific progress, and many other interesting topics.

- Rudy Kahsar’s essay on The good life and the mere life.

Footnotes

-

Here is a relevant excerpt from the Deutsch Files II where Deutsch argues why clashes between ideas result in even better ideas: “…a clash of ideas is very beneficial even if they are never resolved. Even if the parties with the ideas never agree, because when the ideas come into conflict with each other, almost without the people knowing it or wanting it, they get changed. Because even if you come out of an argument saying, “Oh, I’ve really showed it to them!” right? What you mean is, you’ve thought of a new angle, which you didn’t have before going into the discussion. You’ve thought of a new angle on your own view, which makes you more sure of it than before. And, although it’s not good to be sure of things, this change, this way of changing, the confrontation between ideas as being beneficial because they cause change in the ideas is also a beneficial side effect of Popper’s concept of a problem.” ↩